Please also visit Short Stories

Ecumene for Pathfinder 2e

A fantasy setting for the adventurer of Late Antiquity and the sunset of the Classical era

-

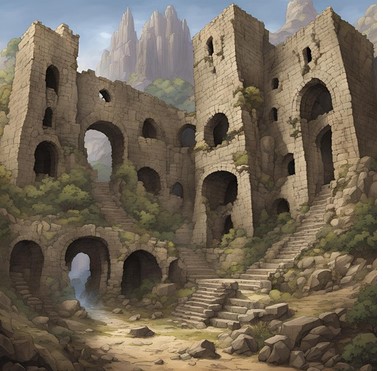

Sample Dungeon #1: Ruins

“That rubble in the distance was once Halicarnassus, the jewel of the Anatolian coast. Those crumbled walls were once temples, towers, fortifications, and homes. They look so solemn there, like something out of a demigod’s legend. The remains of the city, you have heard from many travelers over many years, is full of the wealth…

-

SD #2: Upper Floors

The stairs leading up to the raised structure of the Mausoleum proper is at its widest a rectangle of 120 feet (24 squares) by 90 feet (18 squares). 24 steps lead upwards and inwards towards what could be called the first floor, where the platform upon which the upper chamber, guarded by its grand wooden…

-

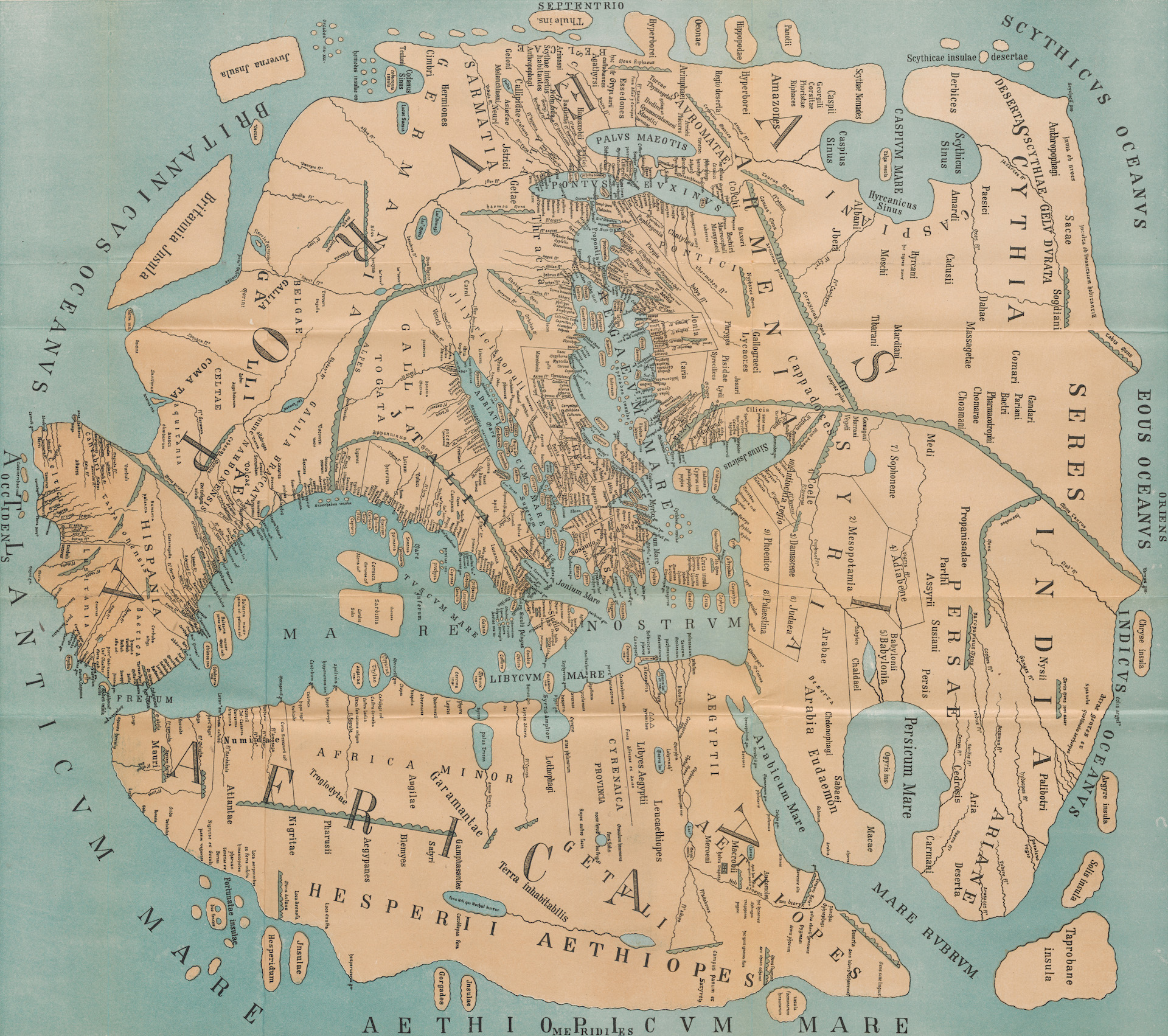

Lore Page #1: Orbis

-Map of the world according to Pomponius Mela, as designed by Konrad Miller “It was the thousand and one hundred and thirty-first year from the founding of the City . . .” -Saturninius Salustianus, Neoplatonist scholar “It was the six hundred and ninetieth year from the dawn of Iskandar . . .” -Shapur Sakanshah, governor…

-

DD #2: The ABΓs

This entry will be rather unfocused, as there are a lot of things regarding ancestries and classes I feel must be mentioned, few of them having much relation to each other. However, if stray thoughts, concerns, and ideas can be gotten out of the way here, the next entries can be much more cohesive, and…

-

LP #2: Gentes

“The Serpent-men are known to be as wily as they are powerful. Perhaps this task is better suited to the Lords of Odisha.” -Report to Samudragupta, regarding a failure to pacify the eastern coast The peoples of the ecumene are many; their forms, innumerable. Many philosophers, priests, and thinkers have wondered as to the origins…

-

DD #3: On the Gods

Before the dev diary begins in earnest, I think it worth clarifying that the lore pages are not written with an omniscient perspective. By the language used, I tried to imply that they were being written by the hand of a historian of the period’s perspective on the world. Obviously, Yazatas are not the “slaves”…

-

Dev Diary #1: Overview

-Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and India in the 4th century, according to Ollie Bye “Ecumene” is a Latinization of the Greek term “Oικουμένη (Oikoumeni)”, and refers to the breadth of the world as the Greeks knew it. Within the breadth of this setting, magic may lift the great stones that assembled the Great…

-

LP #3: Cultus Deorum

“When we beheld the Great Pantheum of Iulianopolis, before it we made three great sacrifices in thanks; to Brahma Fabricator, for our wealth, to Mercurius Sobrius for our safety on the road, and to Mithras Tauroktonos for our honest kin.” -Journal of a Syrian merchant Where there reside men, there reside gods. Gods defend all…